Introduction of the Panama Canal

- Overview of the Panama Canal’s significance in global trade and engineering.

- Key stats: length, location, and importance since its inception in 1914.

The Panama Canal is not just a waterway; it’s a testament to human ingenuity, perseverance, and the determination to conquer natural and engineering challenges. Connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the canal has redefined global trade routes since its inauguration in 1914. This engineering masterpiece spans 82 kilometers (51 miles) and saves ships thousands of miles of travel, making it an indispensable artery of global commerce.

In this detailed exploration, we delve into the canal’s fascinating history, the challenges faced during its construction, its economic importance, and the lessons it holds for the future. Let’s navigate through the story of this modern marvel, celebrating both its triumphs and the sacrifices that made it possible.

Historical Background: Dreams of a Transoceanic Passage

Early Aspirations: Visionaries of the Past

The idea of a canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans wasn’t born in the 20th century. As early as the 16th century, explorers and empires recognized the strategic significance of the narrow isthmus of Panama. Indigenous peoples of the region already used paths across the landmass for trade, inspiring the Spanish when they arrived in the 1500s.

In 1534, King Charles V of Spain commissioned a study to assess the feasibility of a canal. The report highlighted the immense potential of a transoceanic route, but the daunting terrain, dense jungles, and lack of advanced technology rendered the project impossible. Instead, Spain opted for overland transport routes to transfer goods between oceans, a method that remained in use for centuries.

The Isthmus’ Role in the Age of Empire

By the 18th and 19th centuries, as European empires expanded, the Isthmus of Panama became a key point in global maritime strategies. The Spanish Empire used the isthmus as a pivotal link in its treasure fleet routes, transporting wealth plundered from the Americas to Europe. However, the journey was slow and perilous, emphasizing the need for a permanent solution.

The California Gold Rush of 1849 reignited interest in the canal. Thousands of prospectors flocking to California sought quicker routes, making the prospect of a canal more urgent. The combination of growing trade demands and technological advancements set the stage for more ambitious attempts in the years ahead.

The Industrial Age and Renewed Interest

By the mid-19th century, industrialization had revolutionized engineering and transportation. Steam-powered machinery, railroads, and advancements in metallurgy made seemingly impossible construction projects more achievable. The success of the Suez Canal, completed in 1869 under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps, further demonstrated that canals could revolutionize global commerce.

The stage was set for the first serious attempt to construct the Panama Canal. Enthusiasm for the project grew as engineers and nations recognized the immense economic and strategic benefits of a transoceanic waterway.

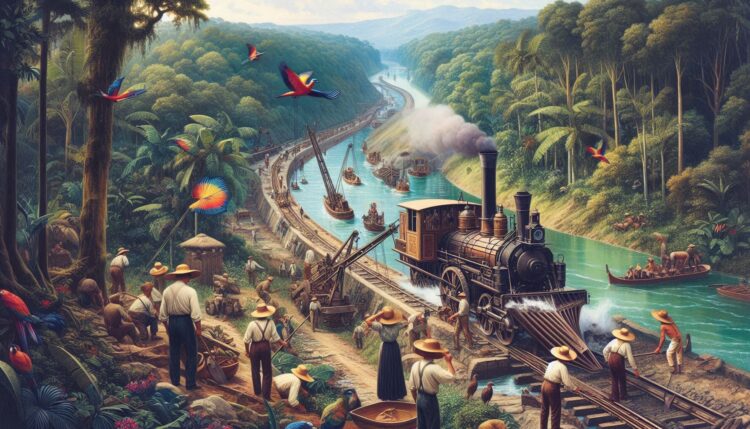

The French Effort: Bold Ambitions and Early Failures

De Lesseps’ Ambitious Vision

Ferdinand de Lesseps, the celebrated architect of the Suez Canal, became the face of the first attempt to build the Panama Canal. His success in Egypt fueled confidence that he could replicate the achievement in Panama. In 1881, under de Lesseps’ leadership, the French launched an ambitious plan to construct a sea-level canal through the isthmus, envisioning it as a seamless passage without locks.

However, the challenges in Panama were vastly different from those in Egypt. Unlike the flat deserts of the Suez, Panama presented dense rainforests, mountainous terrain, and a tropical climate. Despite these challenges, the project initially garnered international support, with investors pouring money into what was hailed as a monumental endeavor.

Major Challenges Faced

The French effort quickly ran into insurmountable problems. The tropical environment proved far more hostile than anticipated. Workers contended with torrential rains, sweltering heat, and a lack of infrastructure to support large-scale operations. The mountainous Culebra Cut, a critical segment of the canal, required massive excavation that pushed the limits of contemporary technology.

Disease was another devastating factor. Yellow fever and malaria swept through the workforce, claiming thousands of lives and earning Panama a reputation as one of the most dangerous places on Earth. At the time, the link between mosquitoes and these diseases was not understood, leaving workers vulnerable to the deadly environment.

Collapse of the French Panama Canal Project

By 1889, the French project was in shambles. Financial mismanagement and underestimation of the canal’s challenges had drained resources. The project collapsed after costing over $287 million and causing the deaths of more than 20,000 workers. Ferdinand de Lesseps faced public disgrace, and the dream of a canal through Panama seemed farther away than ever.

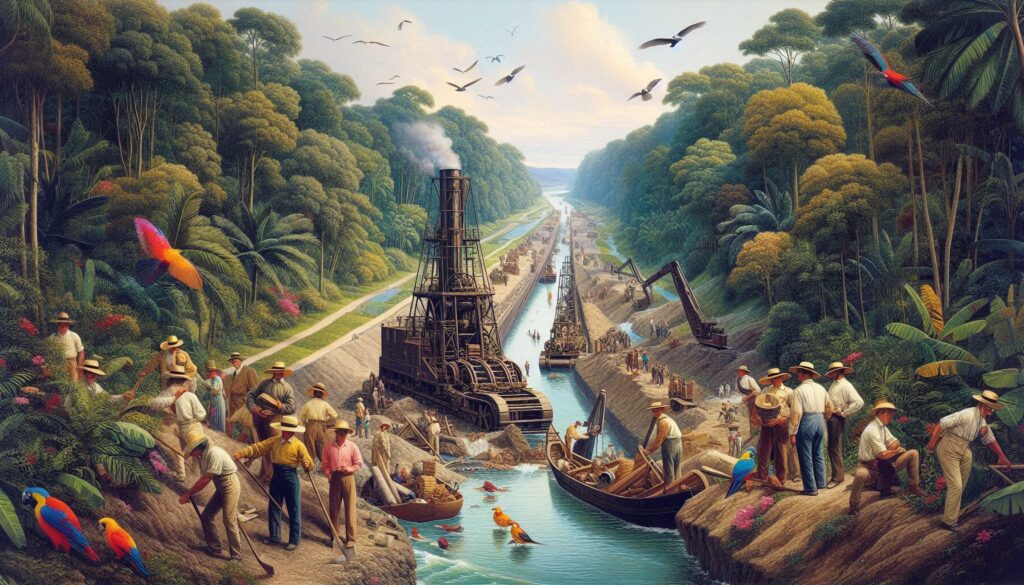

The American Takeover of the Panama Canal Project: A New Chapter

Negotiations with Panama

Following the French failure, the U.S. emerged as the leading advocate for the canal’s completion. Geopolitical interests and the economic potential of the canal aligned with American ambitions. In 1903, after supporting Panama’s independence from Colombia, the U.S. signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, granting them control over the canal zone.

Although the treaty secured American rights to build and operate the canal, it was controversial. Many Panamanians viewed it as an infringement on their sovereignty. Nevertheless, the agreement marked the beginning of a new era for the canal project.

Engineering Breakthroughs

The U.S. approach to the canal differed significantly from the French. One of the key innovations was the decision to build a lock-based canal instead of a sea-level one. This system would allow ships to be raised and lowered over uneven terrain using water-filled chambers. The lock system reduced the need for excavation and made the project more feasible.

The Americans also introduced modern machinery, including massive steam shovels and dredges, to tackle the excavation. Railways were built to transport excavated material efficiently, further streamlining the construction process.

Health and Safety: A Game-Changer

One of the most critical advancements during the American effort was the implementation of health and sanitation measures. Under the leadership of Dr. William Gorgas, a concerted effort was made to combat the spread of yellow fever and malaria. By draining swamps, fumigating buildings, and distributing mosquito nets, Gorgas dramatically reduced disease rates.

The improved living conditions boosted worker morale and productivity, transforming the canal zone into a much safer environment. This focus on health and safety was instrumental in the project’s eventual success.

How the Panama Canal Works: A Technological Wonder

The Panama Canal is often hailed as one of the greatest engineering achievements of the 20th century, and its operation exemplifies ingenious design. By employing a system of locks, reservoirs, and artificial lakes, the canal allows massive ships to traverse the Isthmus of Panama’s challenging terrain in under a day. Here’s how it works:

Locks: Elevators for Ships

The canal’s most defining feature is its lock system, which functions as a series of “water elevators” to lift and lower ships between sea level and the canal’s higher elevations. There are three primary sets of locks: Miraflores, Pedro Miguel, and Gatun Locks. Each lock chamber is approximately 33.5 meters (110 feet) wide and 320 meters (1,050 feet) long, large enough to accommodate substantial cargo ships.

When a ship enters a lock, the chamber is filled or emptied with millions of gallons of water, depending on whether the vessel needs to be raised or lowered. Gravity does the heavy lifting here—water flows in or out from nearby reservoirs without the need for pumps.

Each lock transit takes about 8–10 hours in total, but the time saved compared to traveling around South America’s Cape Horn is immense—roughly 13,000 kilometers (8,000 miles).

Artificial Lakes: The Backbone of the Panama Canal

Gatun Lake, one of the largest artificial reservoirs at the time of its construction, plays a crucial role in the canal’s operation. Created by damming the Chagres River, the lake provides the water necessary for the locks to function and forms part of the navigable route. Ships travel across this expansive body of water before descending through the locks on the other side.

Sustainable Water Management

The canal operates using a gravity-fed water system that relies heavily on rainfall in the region. Each lock transit uses about 200 million liters (52 million gallons) of water, drawn from Gatun Lake and nearby sources. During the 2016 expansion, engineers introduced water-saving basins to minimize freshwater waste, ensuring the canal remains sustainable even as traffic increases.

The Human Cost: Sacrifices Behind the Success Of the Panama Canal Progect

While the Panama Canal is celebrated as a feat of engineering, it is also a somber reminder of the immense human cost that accompanied its construction. The combination of disease, dangerous working conditions, and relentless physical labor claimed tens of thousands of lives over its two major construction phases.

Lives Lost During the French Effort

The French attempt to construct the canal between 1881 and 1889 was marred by staggering human loss. An estimated 22,000 workers perished due to tropical diseases, including yellow fever and malaria, as well as accidents and poor working conditions. The lack of knowledge about mosquito-borne diseases at the time compounded the tragedy. Workers were left vulnerable to infections that swept through crowded camps with little warning.

The American Phase: Improving Conditions but at a Cost

When the United States took over in 1904, they implemented significant health and safety improvements under the leadership of Dr. William C. Gorgas. By draining swamps, fumigating buildings, and addressing sanitation issues, Gorgas’ team eradicated yellow fever in the canal zone and drastically reduced malaria cases.

Despite these advancements, the canal’s construction still exacted a heavy toll. Over 5,600 workers died during the American phase, many of whom were immigrant laborers from the Caribbean. These workers faced discrimination, grueling conditions, and low wages, highlighting the inequities of the time.

The Forgotten Workforce

The majority of the canal’s labor force consisted of Caribbean workers, predominantly from Barbados and Jamaica. They performed the most physically demanding tasks, such as excavation and construction, often for meager pay. While their contributions were critical to the canal’s success, these workers received little recognition or compensation for their sacrifices.

Today, memorials and historical records aim to honor these unsung heroes, ensuring their role in the canal’s history is not forgotten.

Challenges Overcome: Turning Obstacles into Triumphs

The successful completion of the Panama Canal was far from guaranteed. The project faced daunting obstacles, from natural terrain and technical issues to political and financial challenges. However, each hurdle became a lesson in innovation and adaptability.

The Culebra Cut: A Geological Nightmare

The Culebra Cut, also known as the Gaillard Cut, was one of the most challenging sections of the canal. This nine-mile stretch required engineers to excavate through a mountain ridge, removing millions of cubic meters of earth. Landslides were a constant threat, slowing progress and endangering workers.

Modern machinery and innovative engineering techniques eventually overcame these issues, but the process highlighted the sheer scale of the canal’s challenges.

Political and Financial Hurdles

Building the canal required not only engineering expertise but also deft political negotiation. The U.S. had to secure Panama’s independence from Colombia and navigate international disputes to gain control of the canal zone. Financing such a massive project was another significant challenge, as costs continued to escalate throughout construction.

Balancing Nature with Progress

The construction of the Panama Canal dramatically altered the region’s natural landscape. Forests were cleared, rivers were diverted, and ecosystems were displaced to accommodate the waterway. These environmental changes posed challenges for both construction and sustainability, as workers and engineers sought to minimize long-term damage.

The Expansion Project: Modernizing a Masterpiece

As global trade continued to grow, so did the size of the ships that carried goods across oceans. By the early 21st century, the original Panama Canal could no longer accommodate the largest cargo vessels, known as Post-Panamax ships. Panama embarked on an ambitious modernization effort to address this: the Panama Canal Expansion Project, also called the Third Set of Locks Project.

Motivations for Expansion

The original canal, while revolutionary in its time, was designed for ships far smaller than modern supertankers and container ships. The largest vessels that could pass through the canal were termed Panamax ships, with maximum dimensions of 294 meters (965 feet) in length and 32.3 meters (106 feet) in width. As shipbuilding advanced, the size and capacity of vessels outgrew the canal’s capabilities, creating a bottleneck for international trade.

In 2006, Panama approved the expansion project via a national referendum, signaling a new chapter in the canal’s history.

Engineering the Third Set of Locks

The expansion introduced two new sets of locks: Agua Clara Locks on the Atlantic side and Cocoli Locks on the Pacific side. These locks were designed to accommodate Neo-Panamax ships, which are 366 meters (1,200 feet) long and 49 meters (160 feet) wide—significantly larger than the original Panamax vessels.

Key features of the expansion included:

- Water-Saving Basins: These basins recycle 60% of the water used during each lock transit, minimizing freshwater waste.

- Increased Capacity: The expanded canal doubled the waterway’s capacity, allowing it to handle up to 14,000 TEUs (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units), nearly triple the original locks’ capacity.

Completed in 2016, the project was celebrated as a major achievement, reaffirming the canal’s importance in the global shipping network.

Modern Importance: The Panama Canal’s Role Today

A Vital Link in Global Trade

The Panama Canal continues to serve as a linchpin for global commerce, facilitating the transit of approximately 14,000 ships annually. It is particularly crucial for trade routes between Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Common goods transported through the canal include electronics, automobiles, and oil.

The canal saves shippers billions of dollars annually by significantly reducing travel time and fuel costs. For instance, a journey from New York to San Francisco through the canal is about 9,500 kilometers (6,000 miles), compared to the 22,500-kilometer (14,000-mile) route around Cape Horn.

Economic Benefits for Panama

Since gaining full control of the canal in 1999 under the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, Panama has reaped significant economic benefits. The canal generates billions in revenue annually, with toll fees ranging from $800 for small private yachts to over $1 million for large cargo vessels.

This revenue funds infrastructure development, education, and public services, making the canal a cornerstone of Panama’s economy and national pride.

Strategic and Geopolitical Significance

The canal’s location at the crossroads of global trade gives it immense geopolitical importance. Countries and corporations alike rely on the waterway to move goods efficiently. As such, the canal remains a focal point for international diplomacy and strategic considerations, particularly in an era of shifting global power dynamics.

Fun Facts about the Panama Canal

- The Cheapest Toll Ever Paid

In 1928, American adventurer Richard Halliburton swam the length of the canal, paying just 36 cents in toll fees. - The Most Expensive Toll

The highest toll ever paid was over $1 million by the container ship Evergreen in 2016, following the canal’s expansion. - A Transit Takes Less Than a Day

A full transit through the canal typically takes about 8–10 hours, saving ships weeks of travel compared to the Cape Horn route. - An International Workforce

During its construction, workers from more than 50 countries contributed to the canal, making it a truly global effort. - It’s an Environmental Wonder Too

The Panama Canal’s water management system, especially after the expansion, is one of the most sustainable of its kind, relying heavily on gravity and rainwater.

Future Challenges and Opportunities

While the Panama Canal remains a vital artery of global trade, it faces several challenges that will shape its future.

Climate Change and Water Scarcity

The canal’s operation depends heavily on rainfall to supply the freshwater reservoirs that feed its locks. However, changing climate patterns have led to irregular rainfall and water shortages in recent years. Droughts in Panama pose a direct threat to the canal’s efficiency, prompting engineers to explore alternative water sources, including desalination.

Competition from Other Routes

The Suez Canal, which also underwent an expansion, and emerging Arctic shipping routes present increasing competition for the Panama Canal. These alternatives could divert traffic, particularly as global warming makes Arctic passages more navigable.

Balancing Growth with Sustainability

As the canal expands to meet the demands of global trade, it must also balance economic growth with environmental stewardship. Efforts to protect the surrounding rainforest and marine ecosystems are crucial for ensuring that the canal’s impact on the environment remains manageable.

Potential for Further Expansion

With the success of the Third Set of Locks, discussions about additional expansions have already begun. Future developments could further increase the canal’s capacity, accommodating even larger vessels and securing its relevance for decades to come.

Conclusion

The Panama Canal is more than a waterway; it is a symbol of human ingenuity and resilience. From its early conception in the 16th century to its completion in 1914 and subsequent modernization, the canal has been a story of ambition, sacrifice, and triumph.

As it continues to adapt to the demands of a globalized world, the Panama Canal stands as a living testament to what humanity can achieve when faced with seemingly insurmountable challenges. Its history and ongoing evolution remind us that innovation and perseverance can reshape the world in remarkable ways.